Here I attempt to make sense of a methodological quandary that occurs where studies of the design process meet studies of debates as a design process. I started this train of thought in response to feedback from DRS2014.

Debate and design

The direct study of the design process attempts, among other things, to contribute to a better understanding of how design is done by observing that process in action. The object of study is the designer or the design meeting and can be approached by analysis of e.g. think aloud protocols, responses to interview questions or of videos and transcripts from observation of design meetings. The way that the protocol is generated, the veracity of the interviewers responses or the way that the design meeting has been constructed or observed raises some methodological challenges.

The debate as an historical and reflective object

The same kind of methodological questions pertain to my own investigation. In the same way that design studies often means the study of a mediating object ( a transcript for example) the study of political debate does not directly access either politicians or the political process. The object studied is a representation of a debate that has taken place between politicians. At Thatched House this was preserved in the historical record as the proceedings of the meeting. The reasoning behind its circulation can be inferred and in the circumstances it is unlikely to represent a verbatim report. There is context both missing from the document and added by the researcher.

And so it is with the High Speed Two debate. Since 1832 the recording of parliamentary activity has become more accessible and more detailed. In Hansard we are now ostensibly able to access “the edited verbatim report of proceedings” from Parliament. Members’ words are “recorded by Hansard reporters and then edited to remove repetitions and obvious mistakes” before being published the day after the debate took place. If we were interested in studying potential discrepancies between what was actually said and what is eventually reported we are able to access video recordings of the debates. But the video itself is a live edit, created by a director, and the rules concerning how it is produced are themselves subject to debate.

My point here is simply that the record of the debate is not the same thing as the debate, just as a think aloud protocol of a designer is not the same as the thoughts of the designer.It isn’t possible to access the debate directly in any form. The public gallery at Westminster is enclosed behind glass and the sound recorded from the chamber is fed via speakers into the backs of the benches provided. And, as with the interviews of expert designers or their think-aloud protocols, the debate however we access it doesn’t present us with what the participants are thinking nor access to their intentions. We have an historical object from which we can only draw inferences.

A triangle of re-enactment

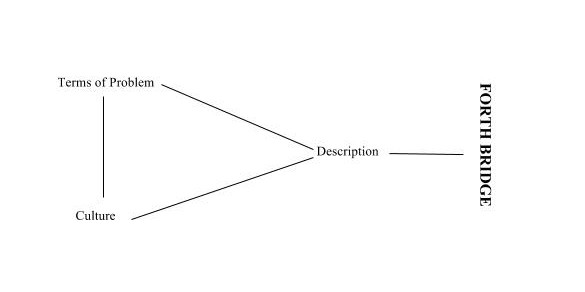

From here I wonder if Michael Baxandall’s analysis of the making of the Forth Bridge offers anything of value. He creates a “triangle of re-enactment” as a way of approaching an historical object, of gaining insight into it and into the intentions of its creator, Benjamin Baker. The triangle looks like this, and my description of Baxandall’s approach follows.

He begins by describing the bridge, treating it as an object that represents a given solution to an unspecified problem. From this description he extrapolates terms such as “span”, “silt” and “sidewinds” which are deemed to represent the objective task or problem. He then generates a further set of terms, such as “steel girder theory” and “bridge types” which comprise a “range of culturally determined possibilities” or the resources that are available to Baker in his approach to the problem.

The process of generation is for Baxandall a critical reconstruction of Baker’s reflection and rationality and leads him on a quest to find what why and how the bridge was built. The description and the explanation are cross-referenced throughout the analysis and in doing so he claims to produce a sharpened perception of both the object as described and the concepts that are drawn from its description.

For Baxandall this triangle offers a critical approach to an object for which there may be no reliable access to the creators intentions other than what can be inferred from their behaviour and from their statements. As an historian studying paintings by dead artists this is a potentially useful tool and Baxandall goes on to apply it to works by Picasso, Chardin and Pierro Della Francesca.

The relevance to design

For a design researcher, and especially one dealing with historical objects, his approach is interesting in a number of ways:

- his concepts – solution, problem, resources – are familiar territory but his simple (or elegant according to Latour, 2005) approach potentially belies the complexity that the design literature has subsequently explored in the relationship between problem and solution.

- as an historiographical approach to an empirical analysis he invites connections to be drawn between design studies, design history and the wider humanities.

- he acknowledges that the object is mediated and that the analysis, however empirical, is constructed

- the object and the researchers description of it occupy a central place in the analysis. This offers a framework that supports the pursuit and description of actors and to the agency of the object but without (necessarily) subscribing to the ANT post-structuralist tendency to overthrow the modernists.

- working within a specific art critical domain he is primarily concerned with the interpretation of paintings where the use of descriptions is a fundamental part of the critical language that doesn’t necessarily carry the same nuance or relevance outside of that field.

In theory

Baxandall’s conception of the object and the relation between it, its creator and the researcher is neatly located between Schon and Latour. The acknowledgment of a reflective practice offers a steadying hand to the more polemical implementations of ANT that are concerned with reconfiguring the world (Latour, 2013) while not necessarily, or at least not explicitly, recognising that the researcher is a part of that world (Yaneva, 2013). It’s not intended to be a model of designing but, if we compare the triangle with an example from design studies (such as Maher and Poon, 1996) it presents a much simpler format and one more suited to the analysis of historical objects that are not sourced from design practice.

In practice

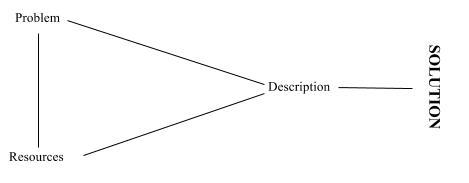

Do the familiarity of the terms used to describe his concepts allow us to use Baxandall’s triangle as a way of approaching different objects? How easy is it to plug different objects into the framework and then consider how these might play out. For example if we place “Thatched House Meeting” in the right hand position how easy is it to visualise its possible relationship to the problem that this object is solving and the resources that are employed in its enactment , including the production of the transcript as one of the resources. This can be done with any number of shifts of focus and scale. An “Act of Parliament”, a “Plan of the London and Birmingham Railway”, a “Petition against the HS2 Bill” or the “Second Reading of the HS2 Preparation Bill”.

On the ground

The problems of repurposing a framework from an art history (which is based on material objects) into design research (which is based on historical events accessed via historical objects) will only become apparent in practice. “Where”, as Baxandall asks, “does the shoe pinch?”.

Baxandall, M (1985), Patterns of intention, Yale University Press

Latour, B (2005) Reassembling the Social, Oxford University Press

Latour, B (2013) An inquiry into Modes of Existence, Harvard University Press

Maher, M and Poon, J (1996) Modeling design exploration as co-evolution, Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, 11 (1996), pp. 195–209

Schon, D, (1983) The Reflective Practitioner, Temple Smith

Yaneva, A (2013) Mapping Controversies, Ashgate

Thanks: to Clive Dilnot and Stephen Boyd-Davis