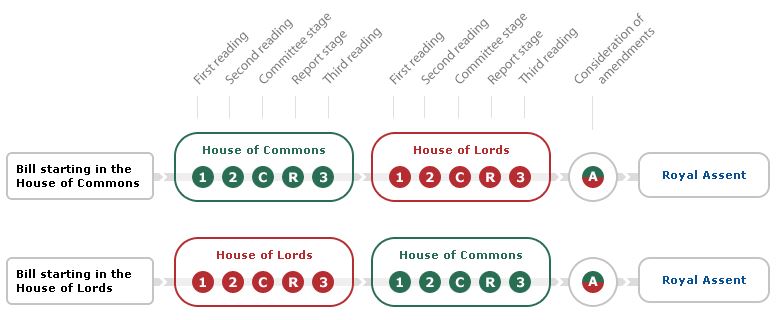

The UK parliamentary process looks like this:

But this representation is complicated by the fact that the system is bicameral: a piece of proposed legislation can be brought into either house first and must pass through both. The main stages that take place in both houses are:

- First reading

- Second Reading

- Committee

- Report Stage and Third Reading

This is repeated in the other house and once a Bill has passed a Third Reading in both it is given Royal Assent and becomes law. A couple of questions have arisen, in working through a thesis that endeavours to look at parliamentary debate from the perspective of design: How does this compare to stages in a design process? And what does it matter if it does?

The first of these is a kind of brake to the full on analysis of the debate transcripts which uses design concepts as a set of sensitising terms for reading the interactions between MPs and takes a step back to look at the process in which the debate takes place. This follows on from my earlier post about the design process as described at the 1962 conference on design methods at Imperial College.

The second question is one of those “so what” questions that will haunt me until I get to the end of this post, at which point I will hope to have something erudite to say about it. But first the easy bit…

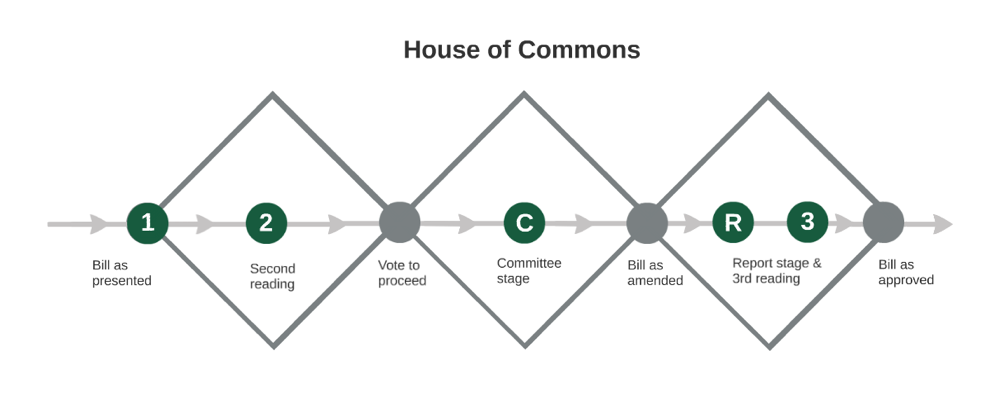

Drawing on the simple Design Council “double diamond design” model that was superimposed on Ken Norris’ morphological process in that earlier post, the stages of a Bill passing through the house of commons looks a little like this:

In this view, the underlying principles of the project are converged into the Bill that is presented to Parliament at the first reading. This is then, in the next stage, subjected to scrutiny by a more divergent group of MPs who participate in the debate at the second reading. The MPs converge on a simple, binary vote of yes or no to decide whether the Bill should proceed and the process is repeated through the subsequent stages. The divergent stages do not always contain the same number or scope of participants and the divergent stages might be a vote or a document that contains the state of the Bill as it has been agreed at that point in the process.

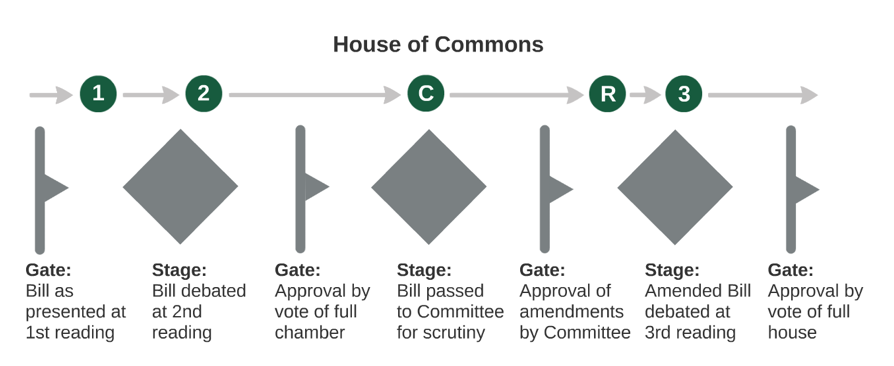

Overlaying a Bill with this generic design model provides a simple description of the Parliamentary process from a design perspective. However, it doesn’t account for the specific stages of the Parliamentary process which determine how the Bill progresses from one stage to the next between these different groups of participants. This progression, marked by the dots in between each diamond, can be compared with the stage gate model of the design process which has become an established prescriptive model of design used in various environments to ensure that a product meets specific criteria before progressing to the next stage of development. Where this development involves high levels of investment, such as when moving from a prototype car into production, then these stages are carefully controlled by senior members of the design team.

In the parliamentary context this product is most clearly seen to be the Bill, which as a piece of legislation, must meet the approval of MPs responsible for its scrutiny. As the Bill also represents the approval of a significant amount of investment public funding this process can also be seen as a series of stage gates controlling the development of the railway line that the Bill describes. This view of the process is represented in the diagram below which expands the points between each of the diamonds in the earlier diagram to reflect the mechanism taking place. The votes that are taken at the end of each debate, either in the full house or in committee, are effectively the gates that control the progress from one stage to the next and these votes, like the decision in a design process, are cast by MPs who are the most senior, elected decision makers in the country.

So, there are some simple comparisons to be made that allow connections to be made between established models of how design works and the formal process of getting a Bill through Parliament. This provides some structural foundations for more detailed comparisons that might be made between what takes place within these stages and how these might then be construed as design activities. It also, beyond any methodological niceties that help to tidy up a sometimes sticky chapter of a thesis, demonstrates how the design of the Parliamentary process appears to be a quite sophisticated series of shifts in perspective that bring different participants together at different times in what might be seen as an attempt to achieve the best possible result in what can be complex, controversial intractable circumstances. Witness Prime Minister’s Question Time to understand why the notion of sophisticated in relation to Parliament is not always an easy claim to make.

And this I think might be part of the answer to that thorny so what question posed above. If looking at Parliament in this way helps us to understand how it works, and helps us to have some faith in the mechanism and those who participate in it then this, in the pursuit of democracy and accountability, is surely a worthy cause. There is also the corollary prospect that, given that the UK Parliamentary process has evolved through numerous reforms and refinements over a number of centuries, there is a possibility that the way this process unfolds might also provide some useful pointers to how design processes in other fields might be improved.